Modelling of Physics Processes and Software Tools

Conveners: Rob Veenhof (CERN), Ozkan Sahin (Uludag University, Piet Verwilligen (Universita e INFN, Bari)

In this WG, a common, open-access, maintainable software suite for the simulation of MPGD detectors will be developed. The existing tools for the simulation of primary ionization, transport and gas amplification will be extended, in particular to improve the modeling at very small scales. An effort will be made in order to integrate the tools into the Geant 4 package to make them easier to maintain and directly applicable within arbitrary geometry and field configurations. Also the modeling of the electronics response to the detector signals has to be improved. This will also make the simulation applicable to systems with very high granularity such as CMOS pixel readout. The tasks are: (1) Development of algorithms (in particular in the domain of very small scale structures); (2) Simulation improvements; (3) Development of common platform for detector simulations (integration of gas-based detector simulation tools to Geant 4, interface to ROOT); and (4) Development of simplified electronics modeling tools.

From wire chambers to MPGDs

Calculations for wire chambers are considerably simpler than calculations for MPGDs: wire chambers have smooth, essentially two-dimensional fields and the electron trajectories follow the electric field. MPGDs on the other hand have three-dimensional electrodes with field-shaping structures not much larger than the mean free path of electrons in the gas.

Field calculations

Whereas fields in wire chambers can in general be calculated with analytic techniques, simulation of MPGDs draws on numeric methods.

Most common are finite-element calculations. These can be performed with commercial software but also with open-source Gmsh Elmer, linked with Garfield++.

A recent alternative is the nearly-exact boundary element method, neBEM, interfaced with garfield and Garfield++.

Microscopic tracking

Electron transport in MPDGs, instead of being a mere matter of integrating a first order differential equation, relies on Magboltz, an electron scattering Monte Carlo for atoms and molecules.

This focus on physics makes the field attractive to students and several theses have been written on the subject.

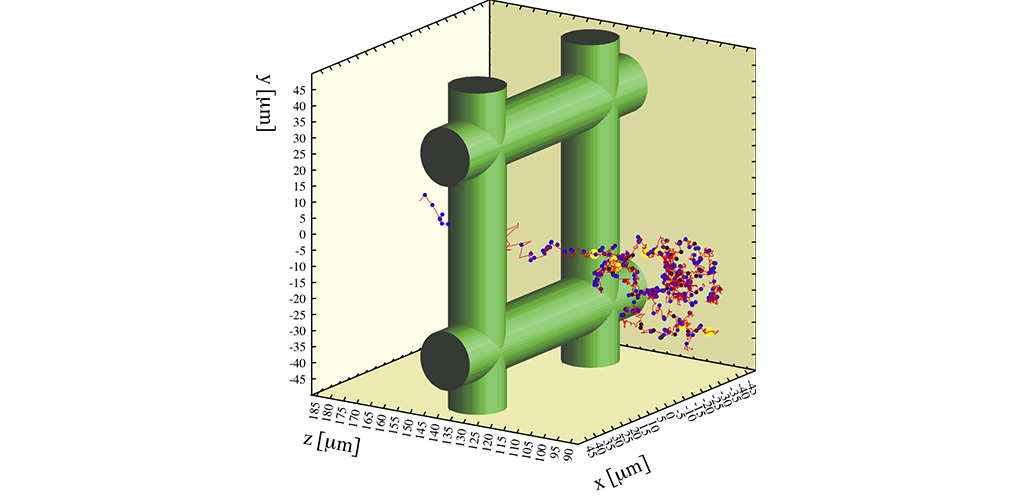

Microscopic tracking of electrons undergoing avalanche multiplication in the vicinity of a micro-mesh.

Excited states

Prior to 2010, the excited states of noble gases were not routinely taken into account when simulating gas-based detectors. Once the cross sections of excitations had been incorporated in Magboltz, the Penning effect could be included in gas-gain calculations. It turns out that the Penning effect increases the gain by a factor of up to 10 in common mixtures. Transfer rates have meanwhile been measured for numerous mixtures.

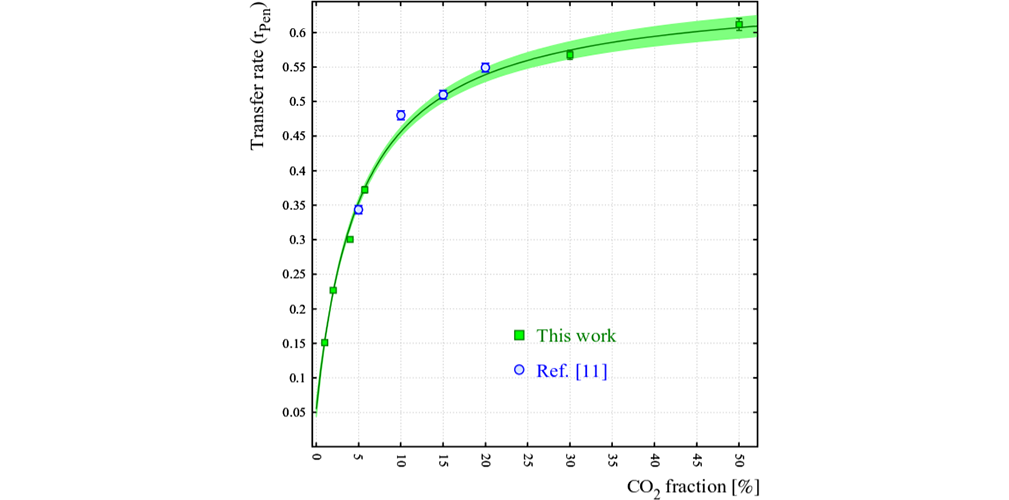

Penning rate in Ar-CO2: comparison of 2010 data and more recent data (Kowalski).

Multiplication

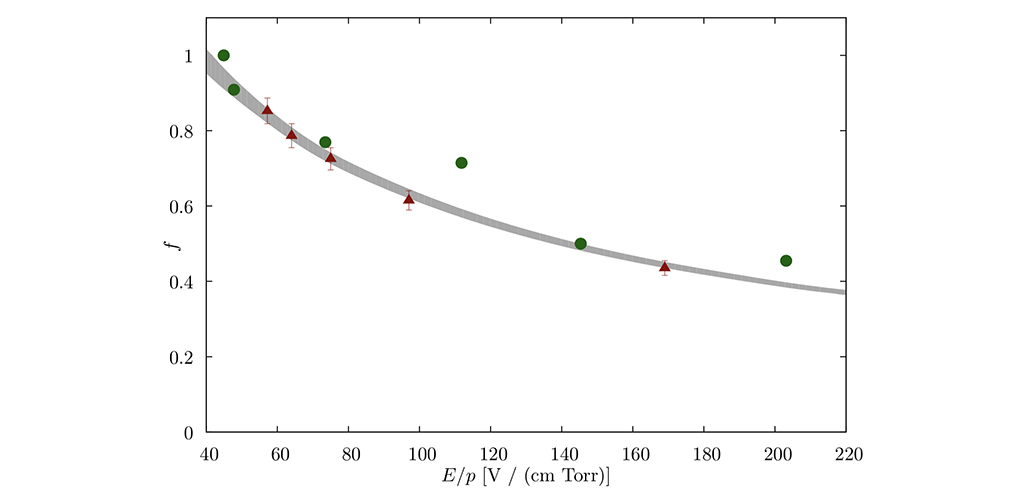

Microscopic tracking can be used not only to work out the trajectories of single electrons, but also to simulate avalanches. This sheds light on gain fluctuations, surface and space charge accumulation, and mesh transparency.

There is in general agreement between measurement and calculation, but the mean avalanche gain in GEMs remains ununderstood.

Parameter f = sigma2/mean2 as a function of reduced electric field E/p for methane. The parameter f describes how much of a hump the avalanche size distribution has. The coloured markers are data and the grey band is MC.

Ion chemistry

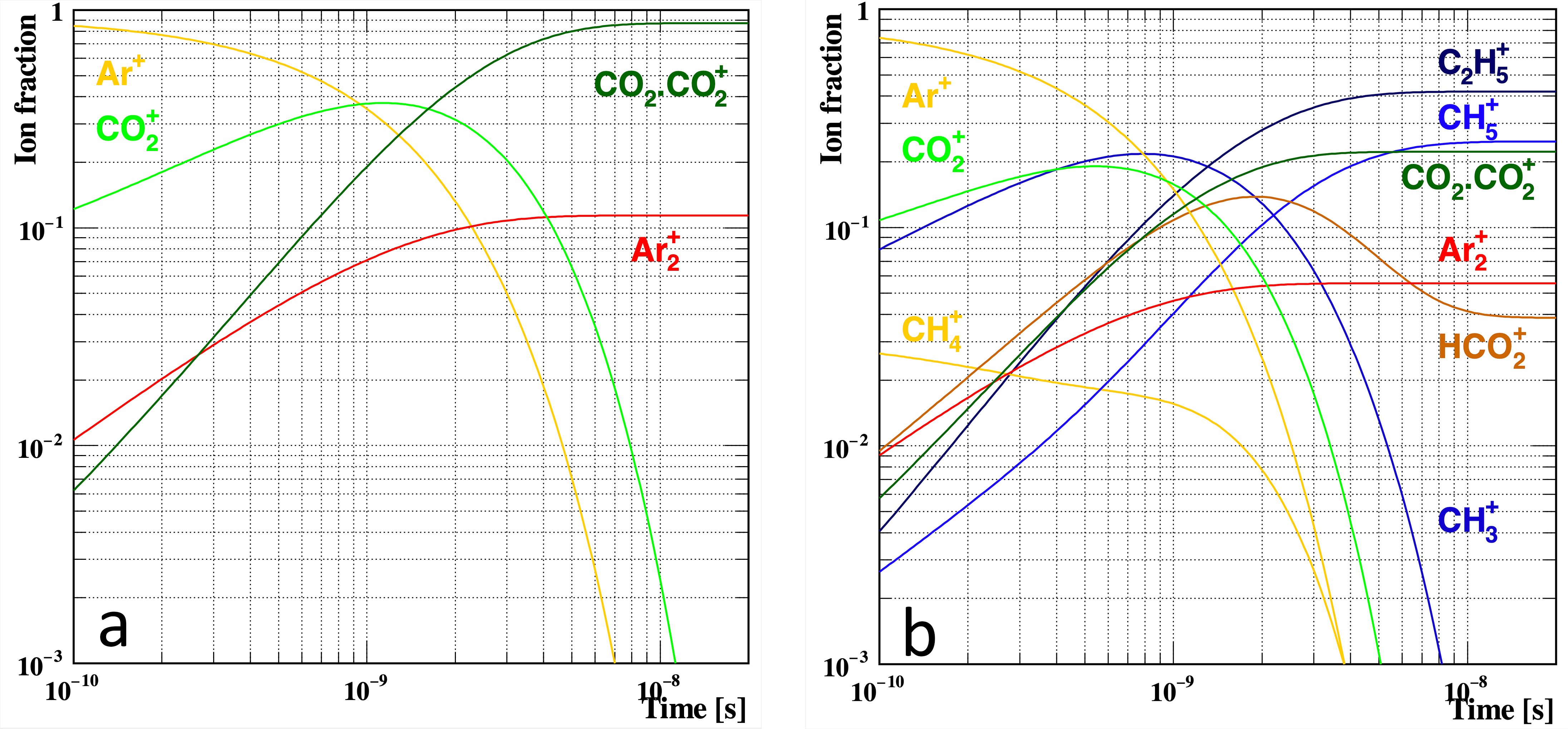

For many years, we have thought that the signal in Ar-CO2 mixtures is generated by Ar+ ions, despite the ionisation potential of CO2. It is now known that there is not only charge transfer but also formation of CO2·CO2+ cluster ions. It so happens that the mobility of the cluster ion in the 70-30 mixture is almost equal to the mobility of Ar+ in pure Ar.

Ion reactions happen for virtually all gas mixtures. They are particularly complex for alkanes. This should be an interesting subject for theses.

Resistive layers

MPGDs nowadays often include resistive layers to enhance robustness and performance. The calculation of the induced current in these devices requires an extension of the Shockley-Ramo theorem. The implementation of this formalism, based on time-dependent weighting fields, in Garfield(++) will be a key line of work during the coming months.

Excited states

When the ionisation potential of the quencher is lower than one or more excitation potentials of the noble gas, collisions between excited noble gas atoms and quencher molecules can lead to additional ionisation. This is called the Penning effect.

Prior to 2010, Penning transfer was not routinely taken into account when simulating gas-based detectors - bit was known that the gain computed with direct ionisation alone, was not accurate.

Once the cross sections of excitations had been incorporated in Magboltz, the Penning effect could be included in gas-gain calculations. It turns out that the Penning effect increases the gain by a factor of 10 and occasionally more, depending on the gas mixtures.

Transfer rates have meanwhile been measured for numerous mixtures. In Ar-CO2 mixtures the transfer probability can be understood in terms of collision frequencies, photo-ionisation, lifetime etc.

[graph] Caption: Penning rate in Ar-CO2: comparison of 2010 data and more recent data (experimental data from Tadeusz Kowalski, model graph from Ozkan Sahin).

However, such is not the case for isobutane and neon mixtures. It has been conjectured that this is because the avalanche electrons lose more energy in collisions than they pick up from the electric field. The avalanche electrons are said to be in a "non-equilibrium state". This mechanism is not yet proven and is worth further study.

Ion chemistry

For years, we have thought that the signal in Ar-CO2 mixtures is generated by the movement of Ar+ ions, despite the ionisation potential of CO2 being lower than that of Ar. Using published reaction rate constants, and looking closer, we found that all Ar+ and CO2+ ions have vanished after a few ns. Some of the Ar+ ions form Ar2+ dimers, but charge transfer converts the majority of Ar+ ions to CO2+ ions.

CO2+ ions turn rapidly into CO2+.CO2 clusters which are held together by charge-induced dipole interactions. Clusters tend to grow by picking up further CO2 molecules.

It so happens that the mobility of the cluster ion in the Ar-70 - CO2-30 mixture is almost equal to the mobility of Ar+ in pure Ar. The same holds mm for the Ne-90 CO2-10 mixture. This explains why most of the simulations were correct - for the wrong reason. This also shows that avalanche-ions are almost never signal-ions.

Ion reactions happen for virtually all gas mixtures. They are particularly complex for mixtures with alkanes. According to the rate constant tables exotics like CH5+ and C2H5+ should be amongst the end-products.

With the identity of the ions understood for most common mixtures, remains working out the mobility of the ions. This should be an interesting subject for theses.

Greenhouse gases

Besides noble gases (Ne, Ar, Xe), CO2 and alkanes, detectors sometimes contain fluorinated gases.

CH2F-CF3 (R134a) and SF6 are used in RPCs. Additives such as CF3Br (Halon 1301) were used in "magic gas". CF4 is added when low diffusion and high drift velocity

are called for. These gases have a high GWP and are in the process of being replaced by more environment-friendly alternatives.

To identify replacement candidates, a systematic programme of measuring velocity, diffusion, gain and attachment, has been submitted to the Swiss funding agency. The gas measurements will (hopefully) be carried out by the ETHZ group which leads the effort. Gas experts are expected to extract the relevant cross sections.

There is ample room for PhD theses.

Last updated on 3 May 2022 (HS, RV).